Bangor In Focus

Bangor Mental Health Institute

|

The Maine Legislature authorized construction of the hospital in the late 1800s after it became apparent the Maine Insane Hospital in Augusta, which opened in 1840, was overcrowded with little relief in sight. The Legislature also saw the need for residents in the northern and eastern regions of the state to have a mental hospital closer to them.

State Sen. E.C. Ryder of Bangor, a member of the Legislature's committee on insane hospitals, called for a new hospital in an 1889 resolution, in which he stated that treating all of the state's residents with a mental illness in one hospital was insufficient.

The House and Senate approved a bill to build a second state hospital in Bangor and Gov. Edwin C. Burleigh signed it. However, the Legislature rejected the recommendation from a special legislative committee for the state to appropriate

$200,000 for the project. A second attempt to pass the appropriation succeeded in 1893.

The House and Senate approved a bill to build a second state hospital in Bangor and Gov. Edwin C. Burleigh signed it. However, the Legislature rejected the recommendation from a special legislative committee for the state to appropriate

$200,000 for the project. A second attempt to pass the appropriation succeeded in 1893.

Because of Hepatica Hill's location away from a busy downtown Bangor but not to the extent it was too far away, the Legislature decided to buy three parcels of land comprising 105 acres on the hill, between State Street, Hogan Road and Mount Hope Avenue on the city's east side. The prevailing belief in psychiatry at the time was patients needed rest away from an increasingly bustling society. Also, society feared people with mental illnesses and thought it best to keep patients out of sight.

With a cost of $250,000, the hospital was the largest construction project in Maine history -- not including the cost to acquire the land.

Construction began in October 1895. During the winter of 1895 and 1896, contractor W.N. Sawyer removed 40,375 cubic feet of earth and 23,628 cubic feet of ledge. To cut costs, construction crews that leveled the top of Hepatica Hill -- named for its abundance of hepatica plants -- used stones from the excavation to help construct the building and to build a 4,000-foot drive from the building to State Street.

The project hit a snag in 1897 when the state ran out of money to continue the project. The Legislature did not appropriate additional money until 1899.

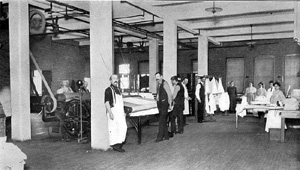

After opening, the hospital's board of trustees kept operating costs down by requiring patients to maintain the hospital grounds, make and fix furniture, do the laundry, and harvest crops from the hospital's fields -- all for no pay. Nurses and attendants had to be single and live at the hospital with the patients. This meant the state did not have to pay salaries sufficient to support nurses and attendants in maintaining their own homes, buying their own food or doing their own laundry.

The hospital sold excess food from its farm to the public and put the revenue back into the hospital. The hospital even generated its own electricity.

Leading up to the hospital's opening, Bangor residents volunteered their time and talents to make the new hospital as hospitable as possible to incoming patients. Women sewed tablecloths and napkins while other area residents donated books and other reading materials for the patients. Others offered to provide the patients with musical and theatrical entertainment. In 1902, nearby Hogan Road resident Sarah J. Lane greeted walking parties of patients from the hospital with refreshments from her orchard.

Leading up to the hospital's opening, Bangor residents volunteered their time and talents to make the new hospital as hospitable as possible to incoming patients. Women sewed tablecloths and napkins while other area residents donated books and other reading materials for the patients. Others offered to provide the patients with musical and theatrical entertainment. In 1902, nearby Hogan Road resident Sarah J. Lane greeted walking parties of patients from the hospital with refreshments from her orchard.

Days before opening, the hospital held an open house that attracted hundreds of people to see what some billed as an advancement in treating mental illnesses.

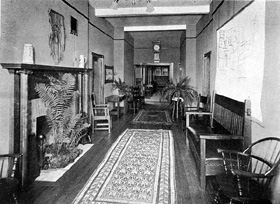

"Everything is as cheerful and homelike as possible," the Bangor Daily News reported in its June 26, 1901, issue. "The whole building, in fact, has rather the appearance of some big hote."

A day earlier, the paper described the new hospital's atmosphere: "Artistic effects in contours and colors are not without their influence in treating disordered minds, and a pleasant, homelike element in the furnishing of a ward will often lessen the distress felt by the patient when first separated from his home and placed in strange surroundings so suggestive to the morbid fancy of good or evil intended toward him."

Although the hospital's official opening was not until July 1, 1901, patients began arriving before then. Albert Coppin of Winterport became the hospital's first patient when he arrived on June 26. Emma Bridges of Bangor arrived June 27, and Flavia Hunton of Milford followed on June 28. On July 1, 70 female patients transferred from the Augusta hospital. On July 6, 75 male patients from Augusta joined them.The Bangor Daily's report of the official opening demonstrated society's attitude toward, and ignorance of, people with mental illnesses.

"First patients have arrived," the July 2 front-page headline said. "Few were violent."

"The exact time of the arrival was not generally known," the paper said, "and for once the curiosity seekers who would otherwise have been out in force were conspicuous by their absence."

The first patients from Augusta arrived by train at 11:30 a.m.

"Upon arriving at the hospital, the majority of the patients spent many hours at the open windows, apparently enjoying the magnificent view from the big building," the paper reported. "All are above middle age, and a stranger would have had difficulty in recognizing in the gentle, white-haired old ladies a lot of dangerous maniacs. It is a strange fact that the most sane appearing person of the entire party was a woman who has for years been kept in solitary confinement."

The nurses

Reception hall, circa 1906. |

Understanding the importance nurses and attendants would be to the social well-being of the patients, Eastern Maine Insane Hospital opened its own two-year nursing school in fall 1901.

"No hospital can suitably carry out its proper function without intelligent, skilled, faithful, and reliable nurses," the superintendent, Dr. George Foster, wrote in his first annual report. "Their whole period of duty is spent among the patients. They live with them. Their influence for good or evil is constantly felt... Not only are the lives of the critically ill in their hands, but the safety of the suicidal depends upon their judgment and watchfulness... So it largely depends upon attendants and nurses whether patients shall become irritated, resentful, and so destructive and violent, or, under the influence of sympathy, kindness, firmness, and tact, develop such orderliness and self-control as may lay the foundation for recovery if the case be hopeful..."

On Nov. 24, 1903, five students were the school's first graduates. They were: Edith Anderson of Surry, Mary Hare of Bangor, Gertrude M. Johnston of Bangor, Mary E. Hickey of Somerville and Pamelia Rigby of Bay Side, New Brunswick.

After a few years, the nursing school required students to work a year at Bellevue Hospital in New York as part of their training. Then, during World War I, nurses were in short supply. Superintendent Carl Hedin asked the Legislature for more money for nurses' salaries.

"Our present scale of wages compels us to pay men and women less for taking care of irresponsible human beings than the average farmer is paying to take care of his livestock," Hedin said. "Under such conditions, we cannot hope to attract the better class of men and the better class of women to our service."

The highly regarded school closed in 1958.

Treatment

Early treatment at the hospital consisted largely of rest, hydrotherapy and working on the farm. Some patients were required to spend up to 18 weeks in bed upon arriving and receive applications of hot and cold water packs, which doctors believed would improve the patients' circulation. These patients often showed "delirium, motor excitement and insomnia," according to Superintendent Foster's 1903 report. Doctors believed that allowing these patients to walk around would exacerbate their symptoms. Foster said it was "common sense" medically to force these patients to rest.

"This is accomplished, as I believe, most effectively, safely and humanely by some such mechanical means as the bedstrap, rather than by the hands of nurses; the human and manual element in opposition usually stimulating the patient in his struggles," Foster said.

The exterior of the hospital's laundry room, as it is today. Builders used stones from the excavation to construct the foundation. |

Foster's preferred mode of treatment for the most excited of patients seemed to contradict the hospital's philosophy, as conveyed by a doctor to the Bangor Daily News in the days before the hospital opened.

"The old notions of restraint and restriction have passed by," the doctor said. "All of the inmates will enjoy almost perfect freedom, although of course the more dangerous ones are always watched. ... We shall do all in our power to make them comfortable and happy."

In addition to rest, psychiatrists also preferred hydrotherapy for patients. In hydrotherapy, patients took long baths of about an hour long, which doctors said helped ease patients' symptoms.

Eventually the hospital picked up on "advancements" in treatment for mental illness, beginning with electroconvulsive therapy -- also known as shock treatment, or ECT -- and lobotomies before psychotropic drugs appeared on the market in the late 1950s.

The hospital also employed an occupational therapy program designed to keep patients busy and their minds off their situation. Superintendent Hedin, who headed the hospital in the 1920s, said occupational therapy enabled patients to take their mind away from their "morbid delusions" so they could again use their mind in a "normal and healthy manner."

Laundry room, circa 1906. |

Patients spent their days playing games by themselves or with others. During the fall and winter the hospital held dances weekly in the auditorium. In 1961, the most popular summer activities were picnics, softball, tennis, badminton, horseshoes, croquet, volleyball, "catchball" and Wiffle Ball.

"The spirit, attitude, attention, ability and response among the patients were found to be exceptionally good," the recreation department reported. "Many developed quite an understanding of the games and for each other's endeavor to participate."

As a sign of the time, prizes for Bingo and other games included cigarettes.

It wasn't until about 1969 that the hospital allowed male and female patients to participate together in sports and sit together at dances. This, recreation department director Bernadette Vollherbst said in her report, "has perhaps proven to be the most outstanding achievement yet."

Patients also went on regular trips to Cadillac Mountain at Acadia National Park, the State of Maine training vessel at Maine Maritime Academy in Castine, the University of Maine in Orono and other towns in the Greater Bangor area. A bus the hospital bought from Army surplus made the trips possible. Patients deemed to be "low-risk" and who worked in the hospital's fields were rewarded with a vacation at Chase's Island in Penobscot Bay, where they mingled with patients from the Augusta hospital.

At the end of the 1960s, the hospital also developed new social treatment programming for patients. One psychologist, Robert Gripp, worked on a new ward program that used the token economy theory to modify patients' behavior. Developed on Ward D-2, which housed 44 women with schizophrenia, the program sought to modify the patients' behavior by granting patients privileges and greater responsibilities in exchange for helpful behavior to the rest of the patients.

The program would not work, though, because of a court ruling a few years later that prohibited hospitals from requiring patients to work without monetary compensation.

Overcrowding

This side view of the hospital shows the incremental additions to the building as the patient population expanded to more than 1,000. Each section is set back from the others to create a sense of open space for patients inside. |

As at most mental hospitals of the time, patients with more serious illnesses, such as schizophrenia, were destined to spend years if not the rest of their lives at the hospital. After a year, it became apparent the hospital would become overcrowded like the hospital in Augusta.

"The condition of the wards is at present so crowded as to seriously impede the proper treatment of curable causes; interfere with the comfort of the quiet, appreciative and orderly class; and make the proper care of the disturbed, disorderly and noisy class more difficult; and their elevation and education out of these disorderly habits well-nigh impossible," Superintendent Foster said in his 1902 annual report.

At night, single-rooms were used as doubles and double-rooms were used for as many as six beds. At times, patients had to sleep in the halls or in the basement. The hospital even had to erect three tents in summer 1905 to provide shelter to the "most disturbed" patients during the day, with two of the tents for females.

"There was a distinct sedative effect as a result of being in the open air and away from the crowded wards during the day," then-Superintendent Philip H.S. Vaughn said in his 1906 report.

After years of begging the Legislature for money to expand, the hospital got its wish in 1907, when the Legislature authorized the construction of an additional women's wing. In late 1906, the hospital had to transfer 43 patients back to Augusta because of overcrowding. But despite the new women's wing, Dr. H.W. Mitchell, the superintendent in 1907, stressed the need for a similar addition to the men's wing.

In the coming year, the hospital's population continued to swell. In 1909, the daily average number of patients rose from the previous year's 280 to 303. The new women's wing opened on Jan. 1, 1909, enabling the hospital to take back the 43 women it had transferred to Augusta in 1906. Construction of a new men's wing was under way. Upon its completion, the hospital's capacity would be 600.

BMHI's "D" Wing originally housed female patients. |

"So much of the welfare and comfort of our patients depends upon the maintenance of nursing force properly selected and trained in the performance of the exacting and trying duties of properly caring for the insane, that it is to be regretted that so many leave the service upon the completion of their two years' course, just at the time when their work is of the highest value," Mitchell said.

As the hospital's population increased, new superintendent Frederick Hills recommended to the Legislature that Maine law allow patients to admit themselves voluntarily to the state hospitals because the cost of staying at a private hospital was often prohibitive. The Legislature accepted the recommendation and on July 1, 1919, patients were able to admit themselves into the two state hospitals.

In the first year of voluntary admissions, 24 men and 14 women walked into the hospital willingly. Nineteen of them admitted themselves for drug addiction treatment. As the stigma of mental illness decreased and the public became more aware of the illnesses, the percentage of voluntary admissions increased. In 1958, the hospital reported that 123 of 490 admissions -- 25 percent -- were voluntary.

The hospital's board of trustees and the Legislature had already begun to combat the stigma of having a mental illness by renaming the hospital from Eastern Maine Insane Hospital to Eastern Maine State Hospital in 1913. The Legislature also renamed the Augusta Insane Hospital, to Augusta State Hospital.

"The effect upon the patients and their friends has been marked and everyone interested in their progress rejoices at the elimination of the word 'insane,'" the trustees said in their report to the Legislature.

However, Superintendent Hills continued to refer to the patients as being "insane."

Even with the name change and expansion, the state found itself behind in supporting its newest hospital. Expansion did little to ease overcrowding. The daily average number of patients climbed from 526 in 1912 to 529 in 1913. The staff was not large enough to provide patients with adequate attention and society began to use the hospital as a dumping ground for the elderly. Although the hospital reported more than 100 deaths on average annually, most of the deaths were of elderly patients admitted by their children.

BMHI as seen from the southeast in its first quarter-century... |

"... Under our social order of living with an increasing tendency for young people to leave their homes, it is becoming more and more difficult for the communities to care for old people suffering from physical and mental infirmities and they are therefore sent to state hospitals for treatment," Superintendent Hedin said in his 1927-28 report.

Indeed, in 1921, 10 percent of the hospital's admission involved patients with "senile dementia."

"Many of these cases were only mildly insane and were brought to the hospital because they had no relatives who were able or willing to care for them," Hedin said at the time. In 1958, the hospital reported that 34 percent of its patients were older than 65.

On March 20, 1928, the hospital reached a then-high of 728 patients despite having a capacity of only 640. Some relief came later that year when construction began on a new male wing that would house 165 patients and 37 hospital employees. Construction of the new wing included a new dining room, which allowed the hospital to convert the older dining room into rooms for patients, bringing the hospital's capacity to 893.

"The overcrowding on the men's side has made it necessary to crowd the patients together in the sleeping rooms and dormitories with beds to such an extent that the male patients no longer have roomy and pleasant day rooms for use during the day," Hedin said.

In addition to overcrowding, the hospital also experienced sanitation problems. Hedin told the Legislature that the hospital's piggery was too close to the wards and attracting rats.

"The present piggery is located too near the wards for proper hospital sanitation and on account of the wooden floors it is also a constant and prolific breeding place for rats," Hedin said. "A new piggery with rat-proof foundation and rat-proof floors should be built at a proper distance from the wards in order to eliminate bad odors and the danger and nuisance of rats."

Hedin also called upon the Legislature to eliminate the requirement that patients admitted to the hospital must first be declared "insane."

"Many patients who suffer from mental disease and who require state hospital treatment are not 'insane' in the legal sense," he said. "To publicly declare a patient 'insane' has also a tendency to aggravate his mental condition, retard his chances for improvement and recovery, handicap him after recovery in finding employment or holding positions, and the label of 'insanity' thus publicly pinned on a patient has a tendency to injure the good name of other members of the family."

Over the years, the hospital's population continued to swell to a peak of about 1,200 patients at the end of the 1950s.

The advent of psychotropic drugs to treat symptoms of schizophrenia -- the most severe mental illness -- manic-depression, major depression and other common illnesses enabled patients to live outside of a hospital setting and in communities with support from social service programs. Today, in 2000, the hospital has fewer than 100 beds -- about 92 percent fewer beds than in the 1950s.

Inadequate staffing

While the patient population increased, the hospital's staffing remained stagnant in comparison. Although there were about 700 patients, there were only two physicians on staff instead of the usual five at times during 1918-1919. The staffing shortage continued throughout the following decades. In 1969, the hospital had only one full-time psychiatrist on staff, three psychologists with master's degrees and four psychologists with baccalaureate degrees. There were only seven social workers.

The hospital's population: 1,133, with the daily average 1,168, which would be an average of 1,168 patients per full-time psychiatrist, 167 patients per psychologist and social worker.

The hospital teamed with the University of Maine's Maine Christian Association to establish a program in which student volunteers were one-on-one companions with older male patients who had been hospitalized the longest. Then-Superintendent Dr. Francis J. Kadi called the program a success. Patients, he said, "had an increased variety of interests, their dress and attention to personal appearance markedly improved and this improvement was reflected in other aspects of the patients' life as well as in their relationships with the college companions."

The hospital today

In 1973, the Maine Legislature changed the name of the Bangor State Hospital to Bangor Mental Health Institute because, as with "insane," "state hospital" had developed a negative connotation. Although the number of beds at the hospital has decreased by about 92 percent since the late 1950s, most of BMHI's buildings are in use as outreach offices for state agencies, such as the Maine Warden Service, the Maine Department of Corrections and the Department of Environmental Protection. Every few years there is talk of closing the hospital, and although that may happen eventually, the hospital still serves an important function for those in central, eastern and northern Maine who need acute care. Even with the opening in 1992 of The Acadia Hospital, a private, nonprofit 100-bed hospital in Bangor owned by Eastern Maine Healthcare, there is still a shortage of hospital beds for people with mental illnesses in the Greater Bangor area. It is not uncommon for patients in the area to be turned away from Acadia and BMHI to be sent to a hospital psychiatric ward in Waterville or even in the Portland area.

In 1973, the Maine Legislature changed the name of the Bangor State Hospital to Bangor Mental Health Institute because, as with "insane," "state hospital" had developed a negative connotation. Although the number of beds at the hospital has decreased by about 92 percent since the late 1950s, most of BMHI's buildings are in use as outreach offices for state agencies, such as the Maine Warden Service, the Maine Department of Corrections and the Department of Environmental Protection. Every few years there is talk of closing the hospital, and although that may happen eventually, the hospital still serves an important function for those in central, eastern and northern Maine who need acute care. Even with the opening in 1992 of The Acadia Hospital, a private, nonprofit 100-bed hospital in Bangor owned by Eastern Maine Healthcare, there is still a shortage of hospital beds for people with mental illnesses in the Greater Bangor area. It is not uncommon for patients in the area to be turned away from Acadia and BMHI to be sent to a hospital psychiatric ward in Waterville or even in the Portland area.

Unfortunately, BMHI continues to carry a strong stigma attached to its mentioning in the general population and it is still often referred to as the "big house on the hill." On July 16, 1987, the hospital was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Should it close, it would be an appropriate site for a museum and monument to the advances in treatment -- social and medical -- of people with mental illnesses.